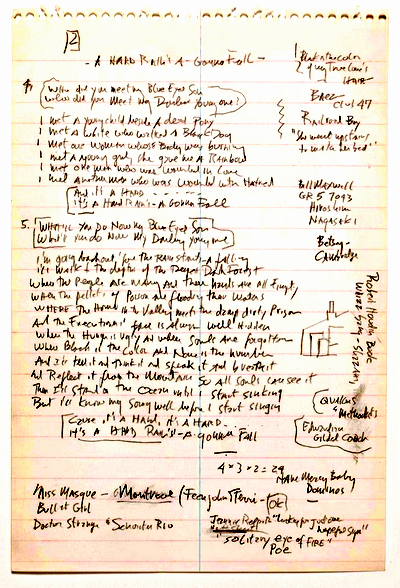

Yesterday I did a post about Bob Dylan’s manuscript for “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” which is being auctioned by Sotheby’s on June 24, 2014 in New York.

I wrote that what I found most interesting about the manuscript was that Dylan had written “Hiroshima” and under that, “Nagasaki” just a few inches from the chorus to the song. I wrote “it’s clear that Dylan meant the song to refer, at least in the chorus, to nuclear annihilation.”

What I found amazing about Dylan writing the names of the two cities the U.S. dropped atom bombs on during World War II, was that he had denied that the song was about what Studs Terkel called “atomic rain,” when Terkel interviewed him in 1963.

Clearly, Dylan was putting Terkel on, I concluded.

In fact, Dylan wrote the song in the summer of 1962, as tensions between Russia and the U.S. were building to the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962 – this was a time when the whole country feared a nuclear conflict.

Dylan told journalist Robert Shelton that he wrote “A Hard Rain” in response to the Cuban Missile Crisis, which wasn’t exactly true: “Every line in it is actually the start of a whole new song,” Dylan said. “But when I wrote it, I thought I wouldn’t have enough time alive to write all those songs so I put all I could into this one.”

The reason I’m coming back to this is that today I got a comment about my post. A reader wrote:

“Interesting that the notations about Hiroshima / Nagasaki would be pulled out from all the other random notations in the song notes as ‘proof’ that the song is about nuclear fallout and nothing else. Surely that theme is an influence here, but I don’t think it means that Bob was lying’ in the interview by saying that meaning expands beyond that. It’s the rare Bob song that is about one thing and one thing only, in my opinion!”

Now I certainly didn’t mean to say or imply that the song is only about nuclear war, but I think it’s pretty clear that one of the meanings of “hard rain,” was “atomic rain.”

Dylan is infamous for misleading or putting on interviewers. Since the early ‘60s he’s said whatever he felt like saying, whether it was true or not. In fact, he purposefully made up fictitious stories about his past. In the fall of 1961 he told CBS that he’d worked in a carnival, which wasn’t true:

Dylan: Yeah, well, I was in the carnival when I was about 13 — all kinds of shows.

CBS: Where’d you go?

Dylan: All around the Midwest, uh, Gallup, New Mexico, Aptos, Texas, and then … lived in, Gallup, New Mexico and …

CBS: How old were you?

Dylan: Uh, about 7, 8, something like that.

“Bob Dylan” is, in fact, a character that Robert Zimmerman created, a character that changed from a scruffy acoustic guitar playing folk singer to a mod rock ‘n’ roller to a Nashville crooner, to mention just a few of Dylan’s personas. One could look at the character “Bob Dylan” as a kind of living montage — a character Zimmerman created and then has been refining and developing ever since.

So misleading Terkel was nothing new, and Dylan has continued to mislead and confuse interviewers in the 51 years since that Terkel interview. That’s part of what “Bob Dylan” does. And in fact, what he’s doing is similar to what fiction writers do. They invent a story that, if they’re good, gets closer to the truth than non-fiction.

Regarding the “other random notations in the song notes” that the commenter brought up, I don’t think they’re all random.

Bob Dylan frequently looked to older songs and poems, sometimes as more than inspiration, when he wrote his own songs.

“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” is structurally based on the question and answer refrain pattern of the traditional British ballad “Lord Randall”, published by Francis Child, according to David Hajdu, author of “Positively 4th Street.”

For his melodies Dylan had been borrowing from old folk songs, so his notations of old folk songs including “Black is the Color (Of My True Love’s hair)” and “Railroad Boy” don’t strike me as random, but rather they may have been songs he was thinking about as he came up with the music for “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.”

Writing the name of the rock ‘n’ roll group, The Dominos, and their hit, “Have Mercy Baby,” shows that even in 1962 when he appeared to be a hardcore folky, Dylan was into rock ‘n’ roll. And the references to comic book super heroes and a line from Edgar Allen Poe show that Dylan was drawing from a wide range of pop culture in addition to old folks songs and poetry as source material for his songs.

Perhaps most telling is that he wrote “Robert Houdin book” on the manuscript. As I wrote yesterday, that “likely refers to a book about the French magician Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin, who is considered the father of modern conjuring.”

Dylan himself has proven to be quite a magician, transforming a middle-class kid from Hibbing, Minnesota into an international rock star, and conjuring up from bits and pieces of pop and folk culture, some of the greatest songs ever written.

[In August of this year I’ll be publishing my rock ‘n’ roll/ coming-of-age novel, “True Love Scars,” which features a narrator who is obsessed with Bob Dylan. To read the first chapter, head here.]

– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post: sounds, visuals and/or news –-