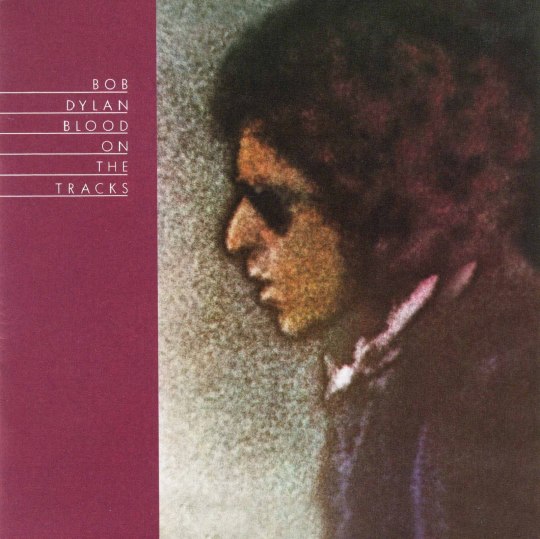

Forty years ago, just after rock critic Jon Landau became Bruce Springsteen’s manager and record producer, his review of Bob Dylan’s Blood On The Tracks appeared in the March 13, 1975 issue of Rolling Stone.

What is most interesting to me about the review, some of which is printed below and the rest of it you can link to, is how, what complains about in critiquing Dylan’s recording style and records — that Dylan makes records too quickly, that he doesn’t use the right musicians, and so on — are the things he made sure Bruce Springsteen didn’t do. What I mean is, Dylan might record an album in a few days and record just two or three takes of a song; Springsteen sometimes would spend a year on a record, recording an infinite number of takes with musicians he worked with for years and years.

Anyway, today we can read Landau’s review of an album that has certainly stood the test of time.

Bob Dylan, Blood On The Tracks

Reviewed by Jon Landau (for Rolling Stone)

Bob Dylan may be the Charlie Chaplin of rock & roll. Both men are regarded as geniuses by their entire audience. Both were proclaimed revolutionaries for their early work and subjected to exhaustive attack when later works were thought to be inferior. Both developed their art without so much as a nodding glance toward their peers. Both are multitalented: Chaplin as a director, actor, writer and musician; Dylan as a recording artist, singer, songwriter, prose writer and poet. Both superimposed their personalities over the techniques of their art forms. They rejected the peculiarly 20th century notion that confuses the advancement of the techniques and mechanics of an art form with the growth of art itself. They have stood alone.

When Charlie Chaplin was criticized, it was for his direction, especially in the seemingly lethargic later movies. When I criticize Dylan now, it’s not for his abilities as a singer or songwriter, which are extraordinary, but for his shortcomings as a record maker. Part of me believes that the completed record is the final measure of a pop musician’s accomplishment, just as the completed film is the final measure of a film artist’s accomplishments. It doesn’t matter how an artist gets there — Robert Johnson, Woody Guthrie (and Dylan himself upon occasion) did it with just a voice, a song and a guitar, while Phil Spector did it with orchestras, studios and borrowed voices. But I don’t believe that by the normal criteria for judging records — the mixture of sound playing, singing and words — that Dylan has gotten there often enough or consistently enough.

Chaplin transcended his lack of interest in the function of directing through his physical presence. Almost everyone recognizes that his face was the equal of other directors’ cameras, that his acting became his direction. But Dylan has no one trait — not even his lyrics — that is the equal of Chaplin’s acting. In this respect, Elvis Presley may be more representative of a rock artist whose raw talent has overcome a lack of interest and control in the process of making records.

Read the rest of this review here.

Bob Dylan – Tangled Up In Blue (New York Version 1974 Stereo)

Bob Dylan – You’re A Big Girl Now (New York Version)

Bob Dylan – Idiot Wind (New York Version 1974 Stereo)

Bob Dylan – Lily, Rosemary & The Jack Of Hearts (New York Version Stereo 1974)

Bob Dylan – If You See Her, Say Hello (New York Version 1974 Stereo)

-– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post: sounds, visuals and/or news –-

—

[I published my novel, True Love Scars, in August of 2014.” Rolling Stone has a great review of my book. Read it here. And Doom & Gloom From The Tomb ran this review which I dig. There’s info about True Love Scars here.]

What is most apparant here is how Landau showed Springsteen the wrong way, his primal spirit, so much alive on stage, hurt by overproducing in the studio (especially Born to Run), whereas Dylan shines through mostly, only to be bogged down for a period in the eighties when he started acting like Springsteen. Sure Dylan made some strange decisions in choices for what songs appeared on an album, but they were motivated by a concept he had in mind. And his first few takes were mostly the best… in case of Blood on the Tracks for a change he improved some things by getting new versions (Tangled up in Blues, Idiot Wind, Rosemary etc) and failed to do so with other songs (Big Girl Now, If you see her), yet at least went for a more varied sound.

And by the way, Born to Run is great, but I would have preferred it without the Wall of Sound… for which Landau might be partly to blame