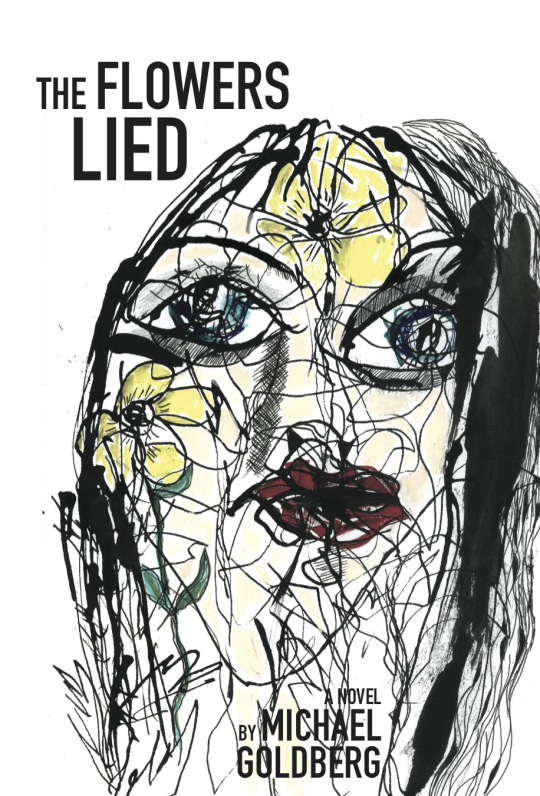

Just wanted to offer a preview of the cover art from my upcoming novel, The Flowers Lied.

The book, a rock ‘n’ roll coming-of-age novel, will be available in October.

If you are interested in reviewing it, let me know and I’ll get you an advance copy. Post a comment letting me know and I’ll be in touch.

Here’s some advance praise:

“There was a time when (rock) music was the living pulse of a generation, when wanting to be a rock critic was a credible dream. That is the era of the Freak Scene Dream Trilogy, an ambitious and ultimately successful attempt at recasting the coming-of-age-in-the-wake-of-the-sixties-experience in innovative but authentic language, Kerouac in the 21st century. It jitters around in ever-accumulating fine detail that traces young love and desire and the pure true heart of the era, the music. It was a pivotal time, and Volume II, ‘The Flowers Lied,’ captures it.” — DENNIS MCNALLY, author of “A Long Strange Trip: The Inside History of the Grateful Dead” and “Desolate Angel: Jack Kerouac, The Beat Generation & America”

“Goldberg presents us with a beautiful evocation of the Seventies where the music wasn’t just the soundtrack to our lives but the auteur of them. Writerman, our hero, drinks and drugs and dances to the nightingale tune while birds fly high by the light of the moon. Oh, oh, oh, oh Writerman!” — LARRY RATSO SLOMAN, author of “On the Road with Bob Dylan”

“Aspiring rock journalist Michael Stein (aka Writerman) returns in the second installment of Goldberg’s Freak Scene Dream Trilogy, picking up the narrative where he left off and fumbling his way across the countercultural landscape of the early Seventies like some less jaded, wannabe-hippie version of Holden Caulfield. This slightly-older-but-not-necessarily-wiser Stein, along with his inner circle of equally confused post-adolescents, is more fleshed-out as a character than in the previous (though superb) ‘True Love Scars.’ As a result the scenarios he finds himself thrust into, not to mention the occasional disaster of his own making, ring with an additional authenticity that will leave anyone who lived through the same era nodding with recognition. Some will even fidget uncomfortably in their seats, as I did—credit to Goldberg’s keen ability to channel his/our own misspent youth while sketching a series of remarkably believable portraits.

“Among the more memorable scenes: a hamfisted attempt to get his rock journalism published in the college newspaper, even more awkward attempts to get laid (that include at least one success, with his best friend’s girlfriend, no less, in a gondola at the top of a Ferris wheel), getting thrown out of a Neil Young concert by one of Bill Graham’s goons, navigating a surreal Halloween party while peaking on LSD, and kibitzing with a popular Lester Bangs-esque rock-crit. Along the way we get cameos from Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, Captain Beefheart, the New York Dolls, Slim Harpo, James Brown, John Fowles, Sartre, Dostoyevsky and Godard. Settle in, crack open a bottle and/or spark a doob, and get ready for an emotional rollercoaster ride. Oh, and don’t touch the Thorens.” — FRED MILLS, editor, Blurt magazine

And a few excerpts from reviews of my previous novel, True Love Scars:

“If Lester Bangs had ever published a novel it might have read something like this frothing debut by longtime music journalist Michael Goldberg… Readers from any musical era will come away with a deeper appreciation of how nostalgia can shape our lives, for better and for worse.” — COLIN FLEMING, Rolling Stone

“Michael Goldberg is comparable to Kerouac in a 21st century way, someone trying to use that language and energy and find a new way of doing it.” — MARK MORDUE, author of “Dastgah: Diary of a Head Trip”

“Penned in a staccato amphetamine grammar, its narrative is fractured and deranged, often unsettling but frequently compelling, an unsparing portrait of the teen condition: assured then despairing, would-be sex god then impotent has-been, an only child battling the wills of his domineering father and interfering mom in the anonymous, suburban fringes of Marin County.” — SIMON WARNER, author of “Text and Drugs and Rock’n’Roll: The Beats and Rock Culture”

“Just call it a portrait of the rock critic as a young freakster bro, coming of age in the glorious peace-and-love innocence of the Sixties dream, only to crash precipitously, post-Altamont into the drug-ridden paranoia of the Seventies, characterized by the doom and gloom of the Stones’ sinister “Sister Morphine” and the apocalyptic caw-caw-caw of a pair of ubiquitous crows.” — ROY TRAKIN, Trakin Care of Business column

– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post –