Ten songs that shook the world!

By Michael Goldberg

I’ve learned quite a few things from the critic and cultural historian Greil Marcus over the years, but maybe the first – and the one I keep coming back to — is that when listening to music, the artist’s intention isn’t so important. What really matters is what you and I, as listeners, hear.

You know, what we get from the music.

“I was never interested in figuring out what the songs meant,” Marcus wrote in the prologue to his book, “Bob Dylan, Writings 1968 – 2010.” “I was interested in figuring out my response to them, and other people’s responses. I wanted to get closer to the music than I could by listening to it – I wanted to get inside of it, behind it, and writing about it, through it, inside of it, behind it was my way of doing that.”

Marcus has been sharing his response to the music since the late ‘60s. In “Mystery Train” and “Lipstick Traces,” “The Old, Weird America: The World Of Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes” and other books he uses art as a doorway, and steps through it to find vast secret histories, histories of America and Europe that mostly hadn’t made it into the history books – at least not in the way Marcus writes.

After reading “Lipstick Traces,” which starts with Johnny Rotten and then proceeds to spin into a history of anarchistic rebellion going back long before Johnny Rotten was born – I haven’t been able to listen to a Sex Pistols or Public Image Ltd. song without thinking of Dada and the Situationists and the May ’68 protests in France and so many other things that Marcus wrote about in that book.

This new one, “The History of Rock ‘n’ Roll in Ten Songs” (Yale University Press, 320 pages), is all about what Marcus hears when he listens to ten songs, and what he hears is unexpected and sometimes revelatory. It’s not any kind of history of rock that you or I have ever read before, because Marcus sees no point in revisiting the same old story that we’ve read numerous versions of since the ‘60s.

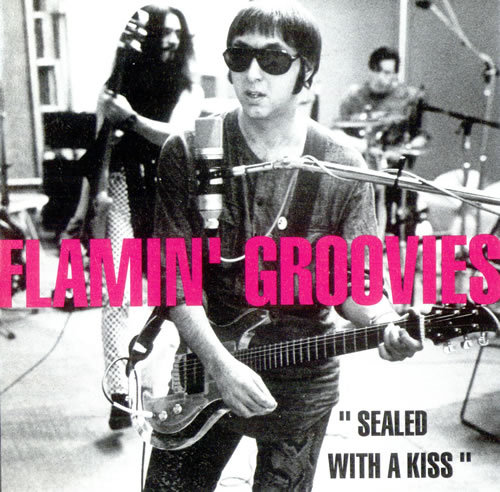

“Shake Some Action” is one of ten songs Marcus writes about in the book.

One of the big ideas in the book is that the chronological history of rock ‘n’ roll – that blues and country begat Chuck Berry and Elvis begat Dylan and the Beatles and so on and so on, is, if not irrelevant, beside the point. Or if not beside the point, well, we’ve been there. We all know, or think we know, the contours of that story. Marcus has a different story to tell.

“Whole intellectual industries are devoted to proving that there is nothing new under the sun, that everything comes from something else – and to such a degree that one can never tell when one thing turns into something else,” Marcus writes in the introduction to his book. “But it is the moment when something appears as if out of nowhere, when a work of art carries within itself the thrill of invention, or discovery, that is worth listening for. It’s that moment when a song or a performance is its own manifesto, issuing its own demands on life in its own, new language – which though the charge of novelty is its essence, is immediately grasped by any number of people who will swear they never heard anything like it before – that speaks. In rock ‘n’ roll, this is a moment that, in historical time, is repeated again and again, until, as culture, it defines the art itself.”

He continues:

“’It’s like saying, “Get all the pop music, put it into a cartridge, put the cap on it and fire the gun,’ Pete Townshend of the Who said in 1968. ‘Whether those ten or 15 numbers sound roughly the same. You don’t care what period they were written in, what they’re all about. It’s the bloody explosion that they create when you let the gun off. It’s the event. That’s what rock and roll is.’ Any pop record made at any time can contain Pete Townshend’s argument. … which is to say that this book could have comprised solely records issued by the Sun label in Memphis in the 1950s, only records made by female punk bands in the 1990s, or nothing but soul records made in Detroit, Memphis, New York City, San Antonio, New Orleans, Los Angeles and Chicago in 1963.”

And more:

“From that perspective, there is no reason to be responsible to chronology, to account for all the innovation, to follow the supposed progression of the form. The Maytals’ ‘Funky Kingston’ is not a step forward from the Drifters’ ‘Money Honey,’ or Outkast’s ‘Hey Ya’ a step forward from ‘Funky Kingston.’ They are rediscoveries of a certain spirit, a leap into style, a step out of time. One can dive into a vault as filled with songs as Uncle Scrooge’s was filled with money and come out with a few prizes that at once raise the question of what rock ‘n’ roll is and answer it.”

I’ve been reading reviews and books by Marcus since the late ‘60s, and he’s dead serious about what he puts on the page. And about what he discovers when he listens to and then writes about rock ‘n’ roll. This is serious stuff, life or death, and if you think music is nothing more than entertainment, well this book is probably not for you.

Reading Marcus is hard work because you have to think when you read his sentences. He takes for granted that you know a hell of a lot about music and art and film and literature. He’s not into coddling the reader. So when he calls his book “The History Of Rock ‘N’ Roll In Ten Songs,” it’s not that you’re going to get the literal history of the music, what you’re going to get is a theory about rock ‘n’ roll, and then ten examples that, in different ways, back up that theory.

So Marcus takes his ten songs and writes an essay about each. He works hard to tell us why these songs matter so much to him, why each in its own way contains the history of rock ‘n’ roll, and why they should matter to us too. And after you read this book, they likely will.

Read the rest of this column at Addicted To Noise, and dig many other great music features, news and reviews.