Bob Dylan has loved the movies since he was a kid.

Not long after his success as a folk singer, in 1965, he made his first movie, letting documentary film-maker D. A. Pennebaker tag along on Dylan’s 1965 U.K. tour. The resulting 1967 film, “Don’t Look Back,” established the sarcastic Dylan persona — to this day the Dylan of “Don’t Look Back” remains iconic.

He let Pennebaker come with him on the 1966 UK tour and the result was “Eat The Document,” a planned TV special that was shelved, but continues the mood established in “Don’t Look Back,” only taken to a more arty and at times outrageous level.

The Byrds’ version of “It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Bleeding” and the Roger McGuinn/Bob Dylan collaboration, “The Ballad of Easy Rider,” were used in 1969’s “Easy Rider.”

Dylan’s fascination with the movies continued. He supplied songs to Sam Peckinpah’s 1973 film, “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid,” and acted in that film as well.

Dylan’s “Things Have Changed” was used in 2000’s “Wonder Boys.” And Dylan’s songs have been in many other films including “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” in 1994’s “Forest Gump” and “The Man In Me” in 1998’s “The Big Lebowski.”

He directed and starred in 1978’s “Renaldo and Clara” and 2003’s “Masked and Anonymous.”

Dylan was influenced by and at times has lifted ideas from films he’s seen.

Below are ten films that had an impact on Bob Dylan. I’ve also included two quotes from Dylan, following the list of films, about movie men who have loomed large in Dylan’s life: director John Ford and actor/director Charlie Chaplin.

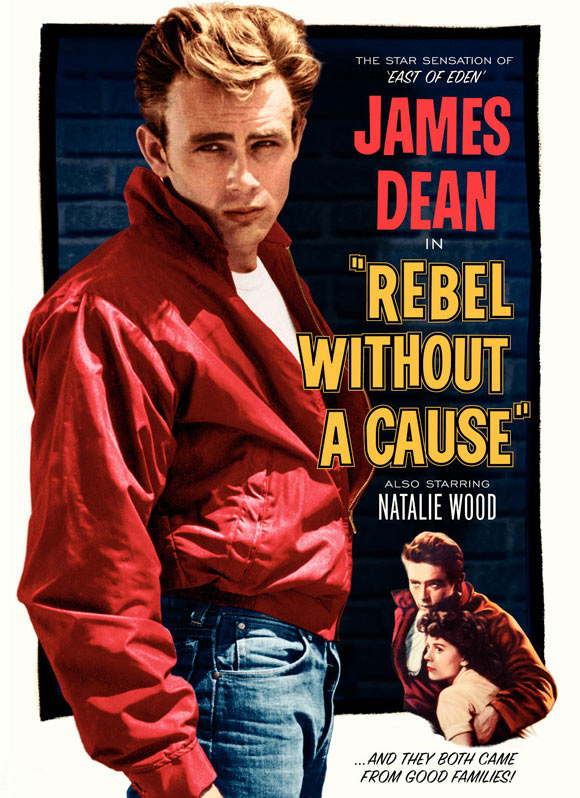

1 “Rebel Without a Cause” (directed by Nicholas Ray)

Bob Spitz writes in “Dylan: A Biography”: It was at the State Theater, in the fall of 1955, that a movie and its enigmatic star gave Bobby the first peek at the combustible properties of attitude and self-expression. On a crisp autumn day, he sat mesmerized by the premier showing of Rebel Without a Cause, a stagy morality play about teenage restlessness in suburbia… It ever the term “born-again” applied to Bob Dylan it was then, following this celluloid revelation. He had gotten a glimpse of the future up on the screen in the form of James Dean, teenage rebel, and it appealed to his sensibility.

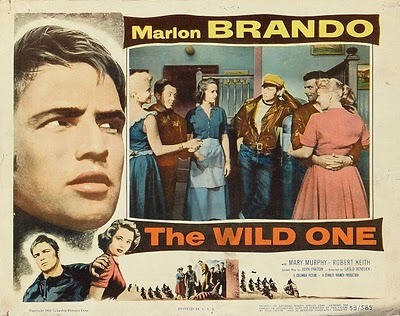

2 “The Wild One” (directed by László Benedek, starring Marlon Brando)

Bob Spitz: Almost overnight Bobby metamorphosed from a wussy squirt into Hibbing’s protopunk. Ge redid himself from head to toe, like a fashion model undergoing a beauty makeover. Along with another impressionable school chum, Bobby made a beeline for Feldman’s basement, the uncharted bluye-collar section of the store, where he picked out stuff Levi’s, black biker’s boots, and a leather motorcycle jacket similar to the one Brando wore in The Wild One.

3 “Blackboard Jungle” (directed by Richard Brooks featuring Bill Haley and the Comets)

Bob Dylan’s high school classmate Larry Hoikkala, after the two of them saw “The Blackboard Jungle”: Bob couldn’t believe it. … he kept saying, “This is really great! This is exactly what we’ve been trying to tell people about ourselves… Looking back that film really changed our lives because for the first time, we felt it was talking directly to us.

From IMDb: A new English teacher at a violent, unruly inner-city school is determined to do his job, despite resistance from both students and faculty.

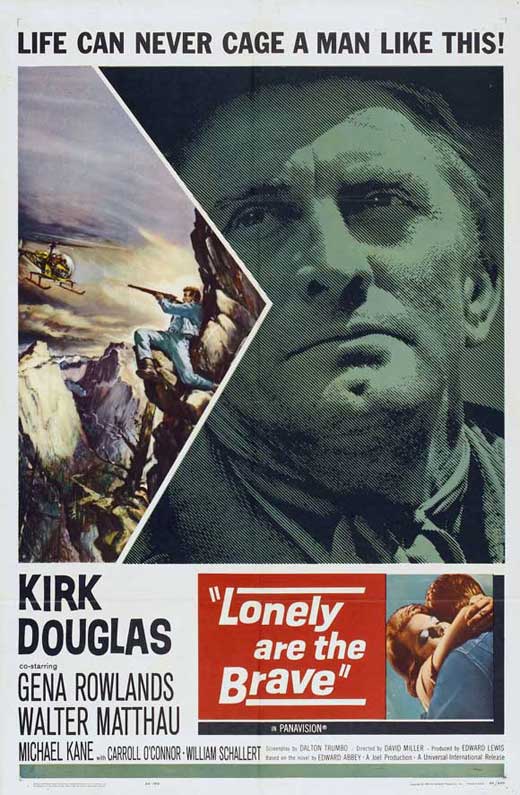

4 “Lonely Are the Brave” (directed by David Miller, starring Kirk Douglas and Gene Rowlands)

From Wikipedia: Lonely are the Brave is a 1962 film adaptation of the Edward Abbey novel The Brave Cowboy. The film was directed by David Miller from a screenplay by Dalton Trumbo. It stars Kirk Douglas as cowboy Jack Burns, Gena Rowlands as his best friend’s wife, and Walter Matthau as a sheriff who sympathises with Burns but must do his job and chase him down. It also featured an early score by legendary composer Jerry Goldsmith. Douglas felt that this was his favorite film.

5 “A Face in the Crowd” (directed by Elia Kazan, starring Andy Griffith)

From Wikipedia: A Face in the Crowd is a 1957 film starring Andy Griffith, Patricia Neal and Walter Matthau, directed by Elia Kazan.[1][2] The screenplay was written by Budd Schulberg, based on his short story “Your Arkansas Traveler”. The story centers on a drifter named Larry “Lonesome” Rhodes (Griffith, in a role starkly different from the amiable “Sheriff Andy Taylor” persona), who is discovered by the producer (Neal) of a small-market radio program in rural northeast Arkansas. Rhodes ultimately rises to great fame and influence on national television

6 “La Strada” (directed by Federico Fellini)

7“La Dolce Vita” (directed by Federico Fellini)

Dylan in Chronicles: There was an art movie house in the Village on 12th Street that showed foreign movies – French, Italian, German. This made sense, because even Alan Lomax himself, the great folk archivist, had said somewhere that if you want to get out to America, go to Greenwich Village. I’d seen a couple of Italian Fellini movies there – one called La Strada, which means “The Street,” and another one called La Dolce Vita. It was about a guy who sells his soul and becomes a gossip hound. It looked like life in a carnival mirror except it didn’t show any monster freaks – just real people in a freaky way. I watched it intently, thinking that I might not see it again.

IMDb on “La Strada”: A care-free girl is sold to a traveling entertainer, consequently enduring physical and emotional pain along the way.

8 Children of Paradise (directed bu Marcel Carné)

9 Shoot the Piano Player (directed by François Truffaut)

Ben Corbett writing about Ranaldo and Clara on about.com: In his Rolling Thunder Logbook, Sam Shepard (who ‘wrote’ the script Dylan’s film Ranaldo and Clara) wrote that when he arrived in New york, Dylan asked him if he’d ever seen Marcel Carné’s Children of Paradise or François Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player. When Shepard asked if that’s the kind of film he wanted to make, Dylan replied, “Something like that.” Both examples of French New Wave cinema, these films would have a huge impact on Dylan’s vision for Renaldo & Clara. In Children of Paradise, the French mime Jean-Louis Barrault plays a role in whiteface, much as Dylan would perform in whiteface during the Rolling Thunder Revue. And the same leitmotif of a flower runs through both films, in Dylan’s case a rose. But more than these similarities, the editing techniques in Carné’s and Truffaut’s masterpieces—jump-cutting, random sequencing, etc.—informed much of Renaldo & Clara’s nonlinear, almost anti-narrative dreamscape qualities.

Bob Dylan, liner notes for The Times They Are A-Changin’:

There’s a movie called

“Shoot The Piano Player”

the last line proclaimin

“music, man, that’s where it’s at”

it is a religious line

outside, the chimes ring

an they

are still ringin

From IMDb on “Children Of Paradise”: This tale centers around the love between Baptiste, a theater mime, and Claire Reine, an actress and otherwise woman-about-town who calls herself Garance. Garance, in turn, is loved by three other men: Frederick, a pretentious actor; Lacenaire, a conniving thief; and Count Eduard of Monteray. The story is further complicated by Nathalie, an actress who is in love with Baptiste. Garance and Baptiste meet when Garance is falsely accused of stealing a man’s watch. Garance is forced to enter the protection of Count Eduard when she is innocently implicated in a crime committed by Lacenaire. In the intervening years of separation, both Garance and Baptiste become involved in loveless relationships with the Count and Nathalie, respectively. Baptiste is the father of a son. Returning to Paris, Garance finds that Baptiste has become a famous mime actor. Nathalie sends her child to foil their meeting, but Baptiste and Garance manage one night together. Lacenaire murders Edouard. In the last scenes, Garance is returning to Eduard’s hotel and disaster as Baptiste struggles after her through crowds of merrymakers, many dressed as his famous character.

Wikipedia on “Shoot The Piano Player”: A washed-up classical pianist, Charlie Kohler/Edouard Saroyan (Charles Aznavour), bottoms out after his wife’s suicide — stroking the keys in a Parisian dive bar. The waitress, Lena (Marie Dubois), is falling in love with Charlie, who it turns out is not who he says he is. When his brothers get in trouble with gangsters, Charlie inadvertently gets dragged into the chaos and is forced to rejoin the family he once fled.

10 “Cat On A Hot Tin Roof”

From Wikipedia: Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is a 1958 American drama film directed by Richard Brooks.[2][3] It is based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning play of the same name by Tennessee Williams adapted by Richard Brooks and James Poe. One of the top-ten box office hits of 1958, the film stars Elizabeth Taylor, Paul Newman and Burl Ives.

From IMDb: Brick, an alcoholic ex-football player, drinks his days away and resists the affections of his wife, Maggie. His reunion with his father, Big Daddy, who is dying of cancer, jogs a host of memories and revelations for both father and son.

In the film Brick Pollitt (Paul Newman) says to Big Daddy’s (Burl Ives): “You don’t know what love means. To you it’s just another four-letter word.”

Dylan wrote “Love Is Just A Four-Letter Word,” which Joan Baez sings some of in “Don’t Look Back” in 1965.

http://youtu.be/OchpaSIYrDY

John Ford

Bob Dylan, talking in Rolling Stone, (Douglas Brinkley interview) in 2009 about John Ford: I like [John Fords] old films, He was a man’s man, and he thought that way. He never had his guard down. Put courage and bravery, redemption and a peculiar mix of agony and ecstasy on the screen in a brilliant dramatic manner. His movies were easy to understand. I like that period of time in American films. I think America has produced the greatest films ever. No other country has ever come close. The great movies that came out of America in the studio system, which a lot of people say is the slave system, were heroic and visionary, and inspired people in a way that no other country has ever done. If film is the ultimate art form, then you’ll need to look no further than those films. Art has the ability to transform people’s lives, and they did just that.

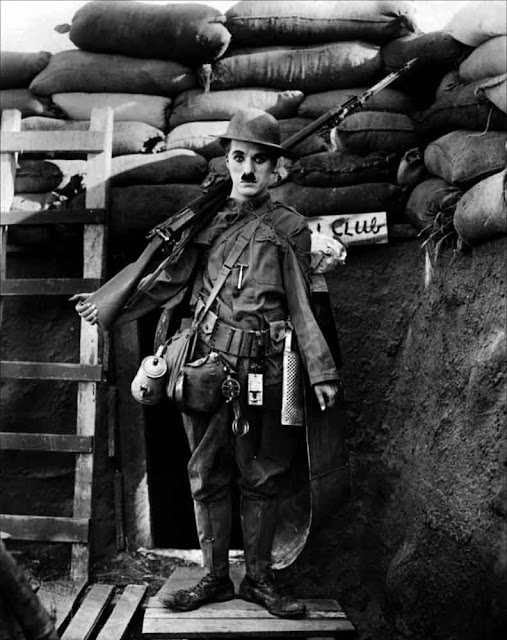

Dylan talking to Robert Shelton about Charlie Chaplin, December 1961, as quoted in Shelton’s book, “No Direction Home: the Life and Music of Bob Dylan”: He [Charlie Chaplin] influences me, even in the way I sing. His films really sank in. I like to see the humor in the world. There is so little of it around. I guess I’m always conscious of the Chaplin tramp.

-– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post: sounds, visuals and/or news –-