Forty-Seven years ago, on December 27, 1967, following just three one-day recording sessions, Bob Dylan released his minimalist masterpiece, John Wesley Harding.

“We can all relax now,” wrote the music critic Ralph J. Gleason in Rolling Stone following the release of John Wesley Harding. “Bob Dylan isn’t dead. He is all right. He is well and he’s not a basket case hidden from our view forever, the lovely words and the haunting sounds gone as a result of some ghastly effect of his accident.

“And his head is in the right place, which, is after all, the best news of all.”

While the best-known song off the album is “All Along The Watchtower,” due to Jim Hendrix’s explosive rock version, every song is a gem.

Dylan recorded in Nashville with producer Bob Johnston, and for all but the final two songs, was accompanied by just two other musicians, drummer Kenny Buttrey and bassist Charlie McCoy. Pete Drake played steel guitar on the two country songs, “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” and “Down ALong The Cove.”

Some comments Dylan made, according to the Drifter’s Escape blog:

“I didn’t intentionally come out with some kind of mellow sound. I didn’t sit down and plan that sound.”

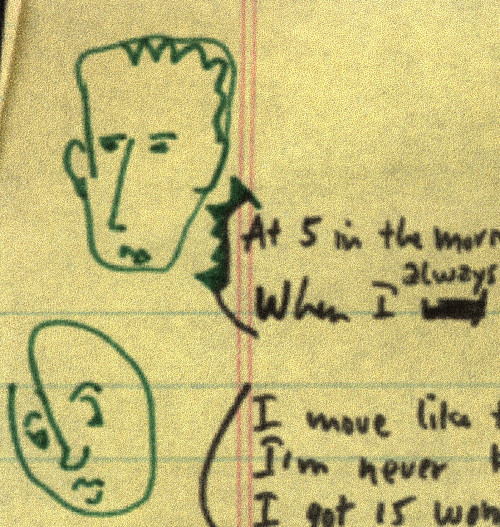

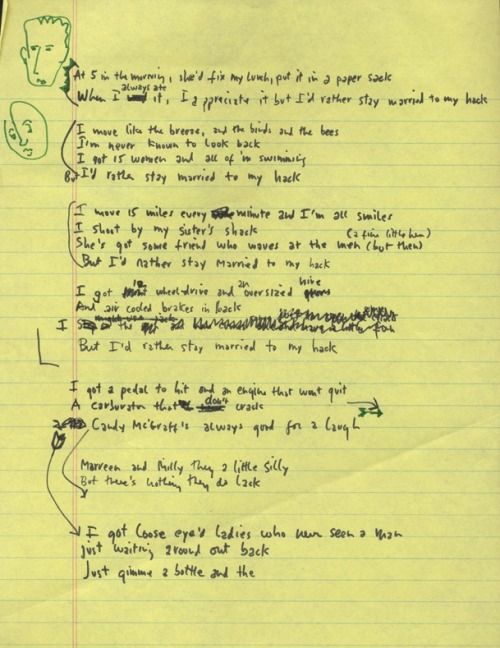

“There’s only two songs on the album which came at the same time as the music…’Down Along the Cove’ and ‘I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight’. The rest of the songs were written out on paper, and I found the tunes for them later. I didn’t do it before, and I haven’t done it since. That might account for the specialness of that album.”

“I asked Columbia to release it with no publicity and no hype, because this was the season of hype.”

“What I’m trying to do now is not use too many words. There’s no line that you can stick your finger through, there’s no hole in any of the stanzas. There’s no blank filler. Each line has something.”

In an interview published in Newsweek in February 1968 Dylan told writer Hubert Saal:

“I was always with the traditional song. I just used electricity to wrap it up in. Probably I wasn’t ready yet to make it simple. It’s more complicated playing an electric guitar because you’re five or ten feet away from the sound and you strain for things that you don’t have to when the sound is right next to your body. Anyway it’s the song itself that matters, not the sound of the song.”

“I could have sung each of them better. I’m not exactly dissatisfied but I’m just not about to brag about the performance. In writing songs I have one great trouble. I’m lazy. I wish I could but you’re not going to find me sitting down at the piano every morning. Either it comes or doesn’t. Of course some songs, like ‘Restless Farewell,’ I’ve written just to fill up an album. And there are songs in which I made up a whole verse just to get to another verse.”

“It [John Wesley Harding] holds together better. I’ve always tried to get simple. I haven’t always succeeded. But here I took more care in the writing. In Blonde on Blonde I wrote out all the songs in the studio. The musicians played cards, I wrote out a song, we’d do it they’d go back to their game and I’d write out another song.”

Dylan talked to John Cohen and Happy Traum in June and July, 1968, for Sing Out!

Dylan talks about ballads and then John Cohen asks if “Wicked Messenger” is a ballad.

Dylan: In a sense, but the ballad form isn’t there. Well, the scope is there atually, but in a more compressed sense. The scope opens up, just by a few little tricks. I know why it opens up, but in a bllad in the true sense, it woudl’t open ujp that way. It does not reach the proportions I had intended for it.

Cohen: Have you ever written a ballad?

Dylan: I believe on my second record album, “Boots of Spanish Leather.”

Cohen: Then most of the songs on John Wesley Harding, you don’t consider ballads?

Dylan: Well I do, but not in the traditional sense. I haven’t fulfilled the balladeer’s job. A balladeer can sit down and sing three ballads for an hour and a half. See, on the album, you have to think about it after you hear it, that’s what takes up the time, but with a ballad, you don’t necessarily have to think about it after you hear it, it can all unfold to you. These melodies on the John Wesley Harding album lack this traditional sense of time. As with the third verse of the ‘Wicked Messenger,’ which opens it up, and then the time schedule takes a jump and soon the song becomes wider. One realizes that when one hears it, but one might have to adapt to it. But we are not hearing anything that isn’t there; anything we can imagine is really there. The same thing is true of the song ‘All ALong the Watchtower,’ which opens up in a slightly different way, in a stranger way, for here we have the cycle of events working in a rather reverse order.

About songwritng Dylan says: It’s like this painter who lives around here — he paints the area in a radius of twenty miles, he paints bright strong pictures. He might take a barn from twenty miles away, and hook it up with a brook right next door, then with a car ten miles away, and with the sky on some certain day, and the light on the trees from another certain day. A person passing by will be painted alongside someone ten miles away. And in the end he’ll have this composite picture of something which you can’t say exists in his mind. It’s not that he started off willfully painting this picture from all his experience … That’s more or less what I do.

— A Days Of The Cray-Wild blog post —